the 1980's mark a era of rebirth for the dacha. millions of middle class urban families wanted nothing more than a peaceful getaway where the pace of life is slow and the space of life is primarily outdoors. russians (and all people of the former soviet union for that matter) seem to thrive in rustic and rural settings. it's as if there's an inherent sense of nostalgia for nature running in their blood. during the 80's, dachniks were also developing a concern about the amount of pesticides found on most of the produce offered in the city markets. with careful planning and plenty of sweat, a family could produce enough fresh produce on a standard dacha plot for an entire year.

i've decided to include a blog post from yelena (transparent.com) because it gives a great glimpse into the 80's dacha life.

I remember very well when my family received our dacha in the late 80s. We all got into our baby-blue «Запорожец» [a relic Soviet car with a 30-horse-power engine and no air conditioning] and drove fifty miles to the entrance to our «садоводо-огородническое товарищество» [dacha community; lit. garden-vegetable community] and another 3 miles over a rutted dirt road to our 600 square meter allotment. And what an allotment it was!

Imagine a flat rectangle of former «колхозная» [belonging to a collective farm] land, depleted of all nutrients and overgrown with «сорняки» [weeds]. The nearest «пляж» [beach] was 30 minutes away and no scenic «луг» [meadow] or «роща» [grove] anywhere near.

All around us were similar newly minted dachas, some already fenced in and sporting freshly built outhouses. These were the first two improvements every sensible dacha owner made –«забор» [fence] and «туалет» [toilet, here - an outhouse].

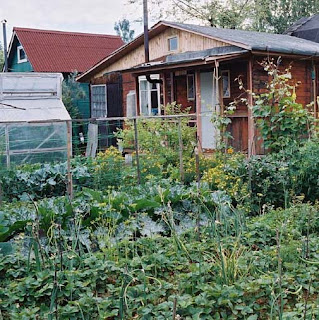

Pretty soon, however, «сараи» [tool sheds] would be erected next to the outhouses; «грядки»[vegetable beds] laid out; «фруктовые деревья и ягодные кусты» [fruit trees and berry bushes] planted. And then the owners would start building their tiny «дачный домик» [cottage].

A few years later, the wasteland would be turned, square meter by square meter, into a beautiful garden with enough fruits and vegetables, except potatoes, to support «среднестатистическаясемья» [an average family] for a year. Every weekend and a few times during the week, this average family would drive their «машина» [car] or ride «автобус» [bus] to their dacha. Once there, they’d plant, water, weed, and harvest until it was time to go to bed or to go home.